Why the 15-hour workweek prediction doesn't materialize

Any discussion of working hours is almost always preceded by a 1930s prediction by economist John Maynard Keynes that by the 21st century we (or at least the West) would be so rich that we/they would only be working 15 hours a week. Keynes was right in that we (again the West) are indeed rich today compared to back then. But he was also wrong in that we are not working 15 hours a week, and nowhere near that. The average workweek in the United States has not varied much from 48 hours a week at that time.

Moreover, the rich, who should have the most free time, are working harder than ever (or maybe this is true only for 2012, when this article was written?). The author of this article, Charles Chu, tries to understand why this is so, why Keynes's predictions have not come true, why everyone, at least in the West, does not work 15 hours a week. These are quite hotly debated questions, and the author notes that he does not have complete answers. However, he puts forward a couple of good theses about our attitude to money, the good life, and human nature to answer these questions.

He addresses these questions through the works of Robert Skidelsky and his son Edward. R. Skidelsky is the author of Keynes's biography and wrote the work "How Much is Enough? Money and the Good Life."

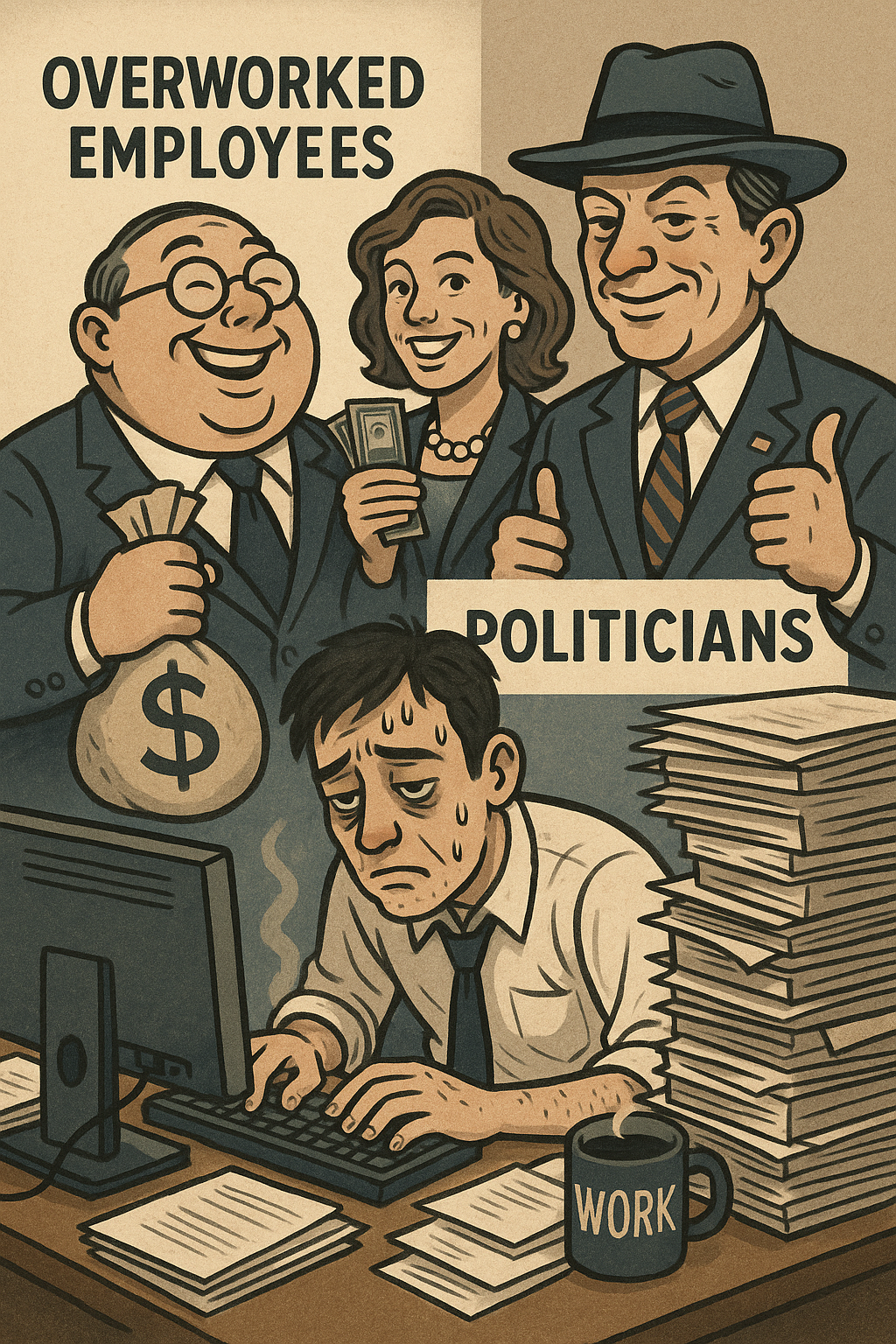

Thus, father and son argue that Keynes's mistake is that he thought that human desires have limits. Keynes's mistake is that he did not distinguish human needs from desires. Moreover, he used these two terms as synonyms in his work. However, needs relate to the satisfaction of the requirements for a good and comfortable life, and therefore have a certain limitation, while desires, which are more of a psychological category, are unlimited in both quantity and quality.

Keynes thought that as we get richer, the value of money would decrease for us. According to him, one day we would be completely satisfied and there would be room to contemplate on higher values. However, we now know well, experience has shown us that material desires have no limit, they expand endlessly, unless, of course, we consciously limit them. Well, capitalism is based on these endlessly expanding desires. It has enriched us, but has deprived us of the most important advantage of getting rich - the consciousness of having enough.

Therefore, the author of this article notes that it is perhaps unfair to blame capitalism for the distortion of this consciousness. Evolutionary theory has taught that all beings have a natural drive to survive and reproduce. And the constant drive for more is part of human nature, not a product of capitalist society.

However, it is also possible that capitalist society in turn multiplies our natural desires. How? One explanation is that the variety of things makes us want more. Shops today offer thousands of versions of the same product, all of which we cannot afford. Advertising, which is everywhere, is impossible to ignore. It offers us products that we didn’t even think we needed. But there is an important and misunderstood reason for the expansion of desires, namely the problem of social status, the satisfaction of which requires the expenditure of endless amounts of money.

The author of the article cites his school years. At that time, he tried to convince his mother to buy him a pair of ripped jeans. His mother refused, because it was December, it was cold, and it made no sense to buy ripped jeans, and for $ 40. The author notes that his mother did not understand his desire, which was based not on the functionality of the jeans, but on social status.

And here is the author’s conclusion that when our ordinary needs are satisfied, money begins to be directed to inflating our status bubble.

For the author, ripped jeans were a dividing line between valuable and worthless, successful and unsuccessful children. Torn jeans were a status symbol, and that was crucial for graduating from school without peer pressure.

Status is no less important for adults. It is precisely status-motivated spending that, according to Skidelsky, Keynes overlooked. Once our ordinary needs are met, our money goes to inflating our status bubble. After a certain point, most of our income is spent on things we don’t need, but which serve to “prioritize” the person who bought them. This phenomenon is called “conspicuous consumerism,” and the author has already addressed this phenomenon in a separate article.

The Short Skirt Question

While it is not difficult to understand how status competition leads to increased spending, it may not be so clear why. One answer to this is what the author calls the short skirt phenomenon. The author lives in Japan, next to a school. Japanese students wear uniforms. Even in the cold winter months, all students wear short skirts. They are supposed to be knee-length, but girls cut them short. Why? Perhaps a short skirt means the same thing to them as ripped jeans do to the author. Wearing a long skirt is a statement of failure, which has the potential to cost you friends. As they say in Japan, "the nail that sticks out gets hammered down".

Of course, there is a limit to the length of the skirt. But there is no limit to spending. If one person has an annual income of $100,000, the other wants to have $200,000. If they earn a few million, they want to earn a few billion. It doesn't matter how rich you become, there is always the opportunity to spend and consume more. In such a situation, it doesn't matter how rich we are today compared to the 1930s. Being at a certain level of the economic hierarchy has become essential: the more you spend, the higher your position.

Moreover, this status competition is in every field: political elections, modernist architecture, etc. And this is a global problem.

The role of culture

However, culture must also be taken into account. Working hours vary from country to country, even if the level of wealth is the same. For example, in the United States, the average number of hours worked per year is 400 hours more than in Germany, and Skidelsky connects this with culture. Immigrants are a big proportion of the United States population and there money is the key to success; In hierarchical culture of Europe there is a restriction on everyone's ability to make money, which led to a lifestyle where making money has not been the ultimate goal. This raises the question for the author whether the American Dream is not to blame for the fact that Americans work much harder today, believing that if they strive, they will achieve anything.

The author notes that this happened to him too. There was a time when he set a goal to become a millionaire by the age of 30, so he did nothing but work every day. If asked why he aspired to it, he might say that he did it so that he would not have to work for the rest of his life. However, the real reason, according to the author, was the result of torn jeans syndrome.

Skidelsky notes that in the past, cultural norms, traditions, and religion have limited this endlessly expanding desire. Religions almost everywhere condemned the endless pursuit of wealth. Morality and tradition were a certain restraining force on the impulses of personal interest. Modern life has eliminated these limitations. Moreover, modern economic and political theory, strives to remain neutral and avoids talking about morality.

So what to do?

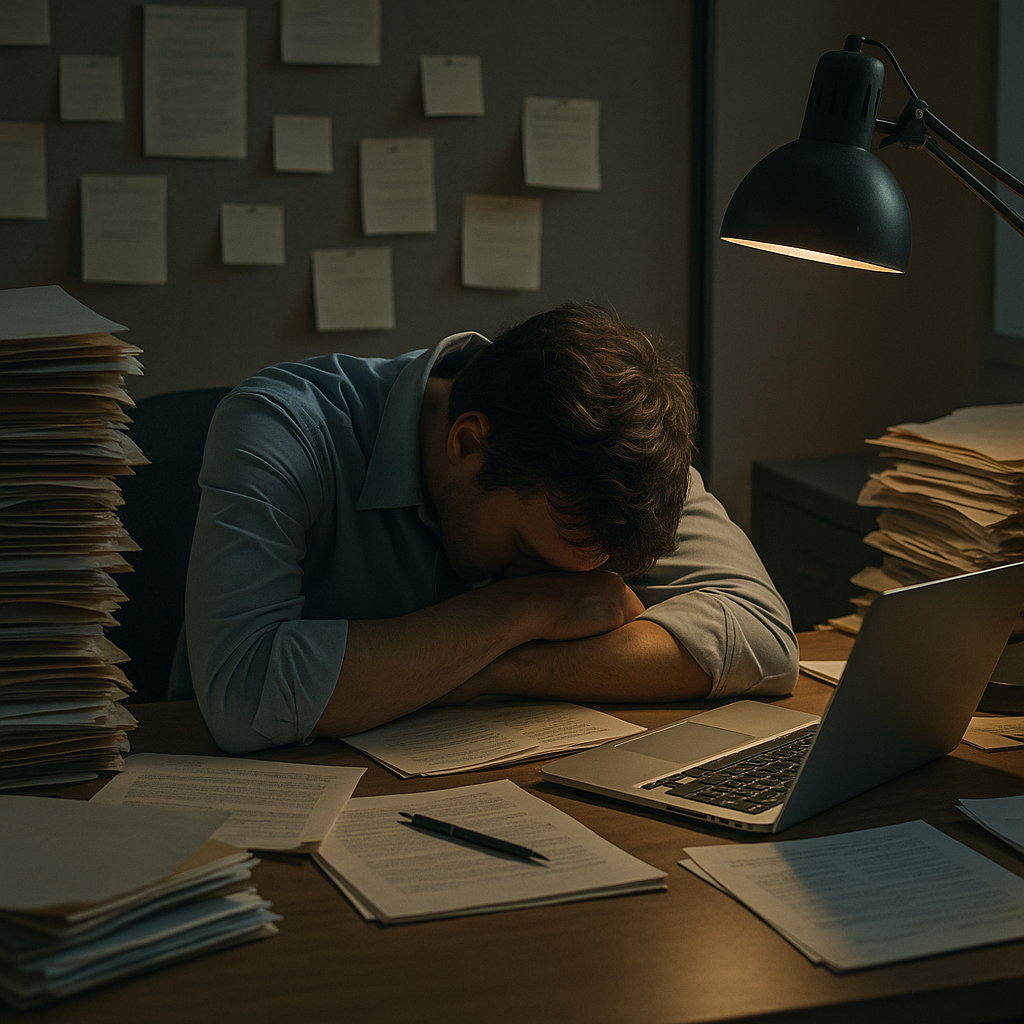

If this theory is true, that a large part of our income is spent on competitive consumerism and showing off status, then it is interesting to see if it is possible to put this game aside and work less than 15 hours a week. The author is a freelancer, so he decided to experiment. In recent months, he has been working one or two days a week. The rest of the days he reads, ponders on political philosophy, plays games with his wife. And he suggests that each of us asks ourselves this question: how much of what I do is done because I am concerned about my status? At the moment, he is not dissatisfied with his finances. Moreover, he realizes that that most of his work was a lie, especially ineffective, because he spent most of his time sitting in front of a computer, because it was a sign of work for him. And now, when he realizes how much energy is spent on accumulating status, he has decided not to play and as a result enjoys his life more. He lives modestly, reads, avoids people who talk about getting rich, being successful or leaving a mark on the world. Of course, he does not recommend that everyone work two days a week, because many employers would consider this unacceptable. But he believes that many people simply do not realize how much of their time and life is spent on building status. Therefore, he suggests asking ourselves: how much of what I do is done for status and would my life be better if I paid less attention to it?

Source (sadly the link no longer works, but you can try reading this one)